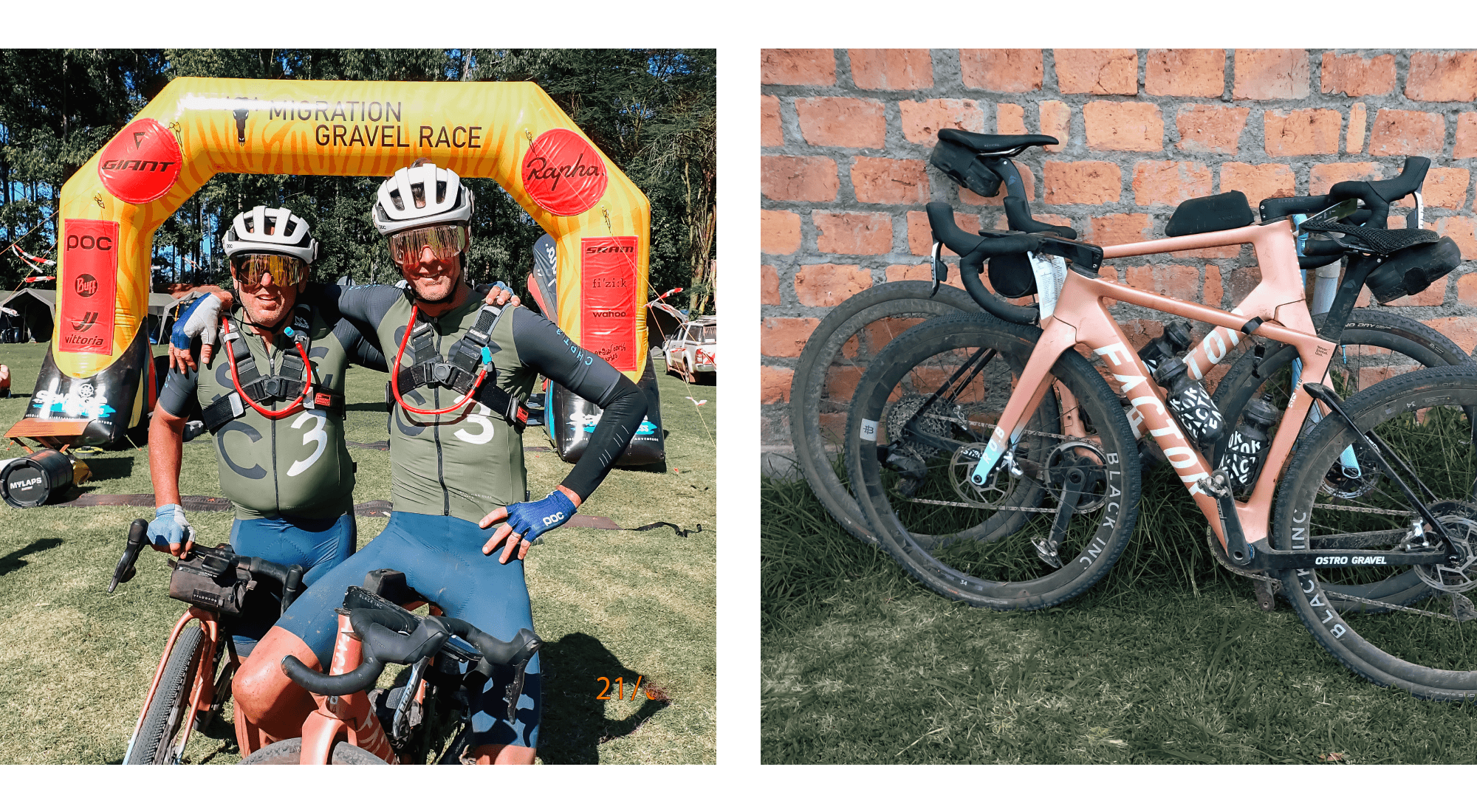

The Migration Diaries: not putting things off anymore

We did it because it was hard

If in the first two blogs, David Millar had been vaguely reminding you of a Joycean hero with his stream-of-consciousness tale-telling, then this final installment of his Migration Gravel Race story will only reinforce and enhance that sensation. Start at the end, jump back to before the beginning, hard graft through the middle, and introspection to the core. David and Rob had a hell of a ride. Four days that will be seared into their memories. And ours too.

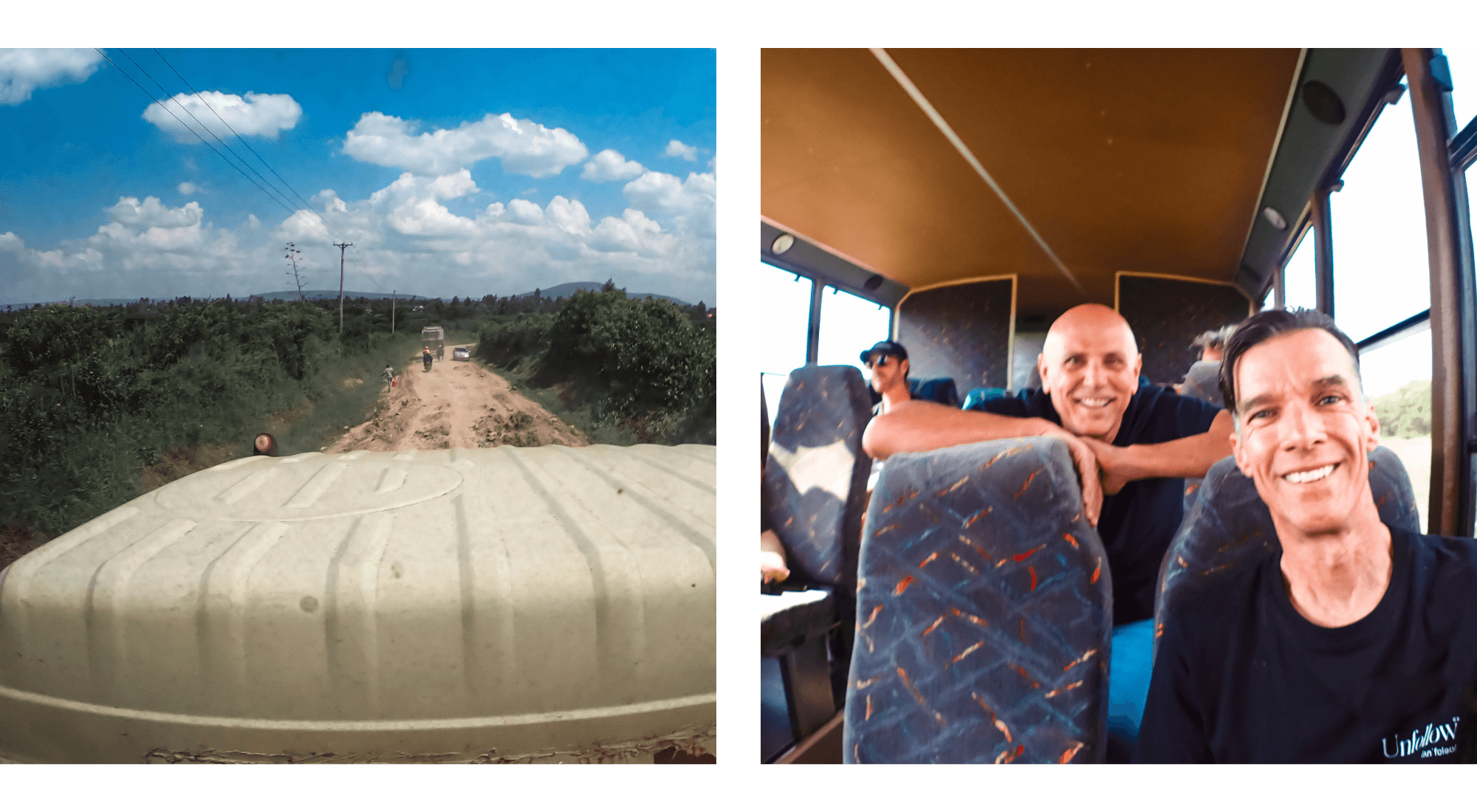

We finished, and I’ll come back to that. I’m ending this diary in the same way I started, sitting on a bus. We’ve been going for six and a half hours and have covered 80km. Our overland convoy of three trucks has so far been stuck in a mud hole, had two punctures, and a dodgy clutch that needed a mechanic. It was slow going and bumpy, not normal bumpy, but a rocking kind, like clinging to a dinghy in a busy harbour. I’ve swapped buses twice, being told another would get me back to Nairobi faster; I have a flight this evening so need to get back ASAP, the first time I swapped was during the third stop for the clutch issue. I got in the bus that was not having its puncture fixed or clutch sorted, sat there for 10mins then watched the other two buses drive away repaired. Masterstroke.

Swapping lines seldom helps

I then swapped back to my original bus at the planned rest stop, they’d got there first and, therefore would be leaving first. That didn’t happen, we all left at the same time, and the “faster” bus I’d been on overtook us. So I’m back to square one, that is, I’m on the last bus. All good though, if nothing else goes wrong (LOL) I’ll make it fine. Literally, as I typed that we hit a hill and the speed dropped to about 10 km/h…

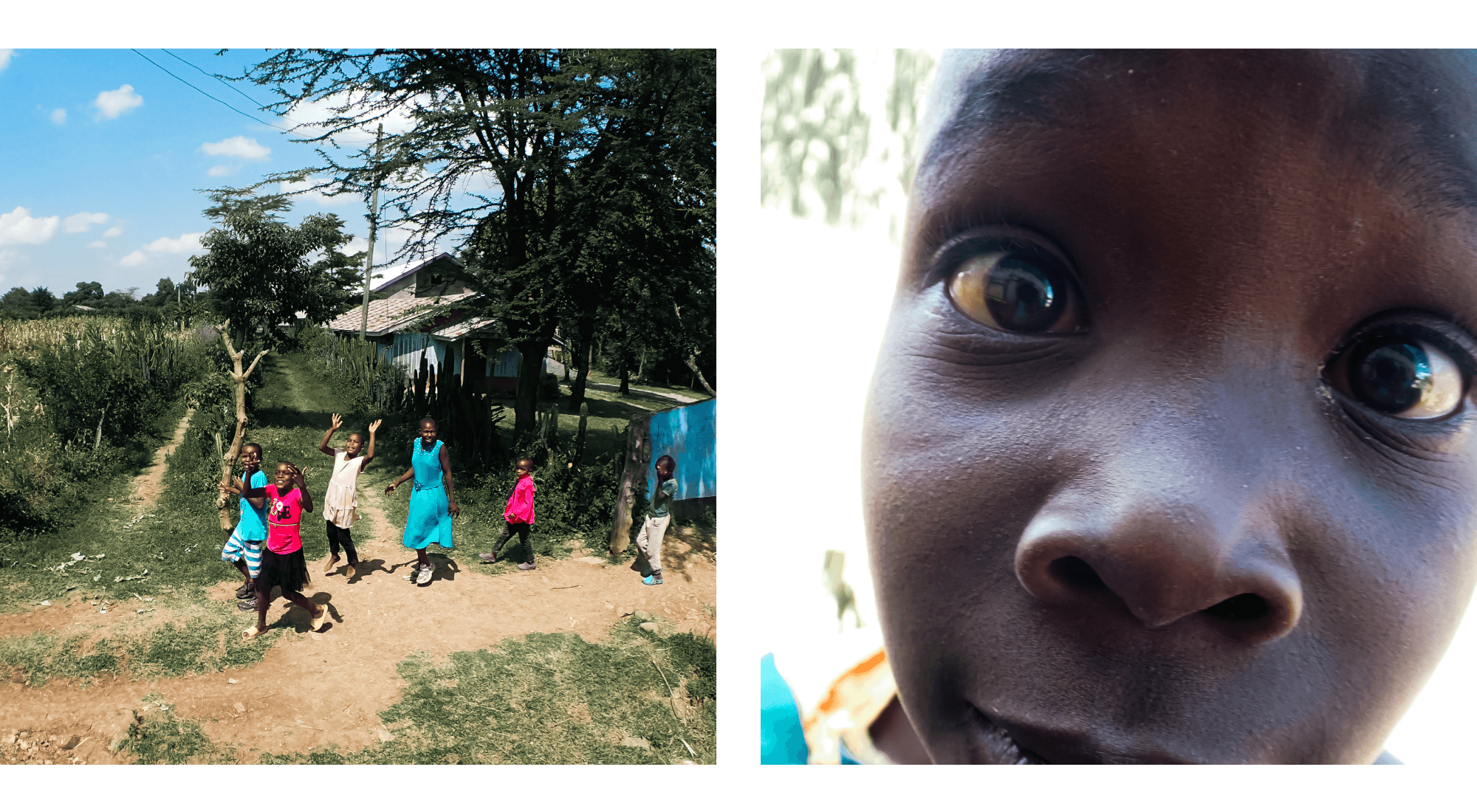

It’s all been very chilled, with no bad tempers rising, it would appear everyone has had a paradigm shift regarding what stresses them - in other circumstances, this journey might have rubbed people up the wrong way; that’s not happening. Even when we were stuck for nearly 90 minutes with the mud hole saga, which happened within the first hour of leaving base camp, everyone just hung around patiently. Loads of local villagers, mostly kids, came and hung with us to watch the trials and errors of removing the truck from the quagmire.

Damian from POC ended up playing football with some boys. The football was some indistinguishable red material shaped into a ball and held together with string, meanwhile, I was sitting with some girls in the shade, letting them take photos with my cameras. It was all very peaceful, almost Zen. No sooner had we got out of the mud, the punctures came, we took them in our stride, as we did with the clutch issue and garage stop. Mere trivialities after the previous four days.

Suffering takes the edge off

It seems that the entire Migration Race field has had the edge taken off them. 180 started: 40 signed up for the shorter Zebra route, and 140 for the longer distance Leopard of which only 37 completed. 25 DNFs and everyone else finished a combo of Zebra x Leopard. I was one of the 37 who completed the full Leopard course. I was awarded a wonderful belt for the accomplishment that I’ll treasure for the rest of my life, although it took me being pushed to the very edge of my existence on Stage 2. I think everyone is quite humbled by the whole experience, not just the course and demands put on each of us, but also what we’ve seen and where we’ve been.

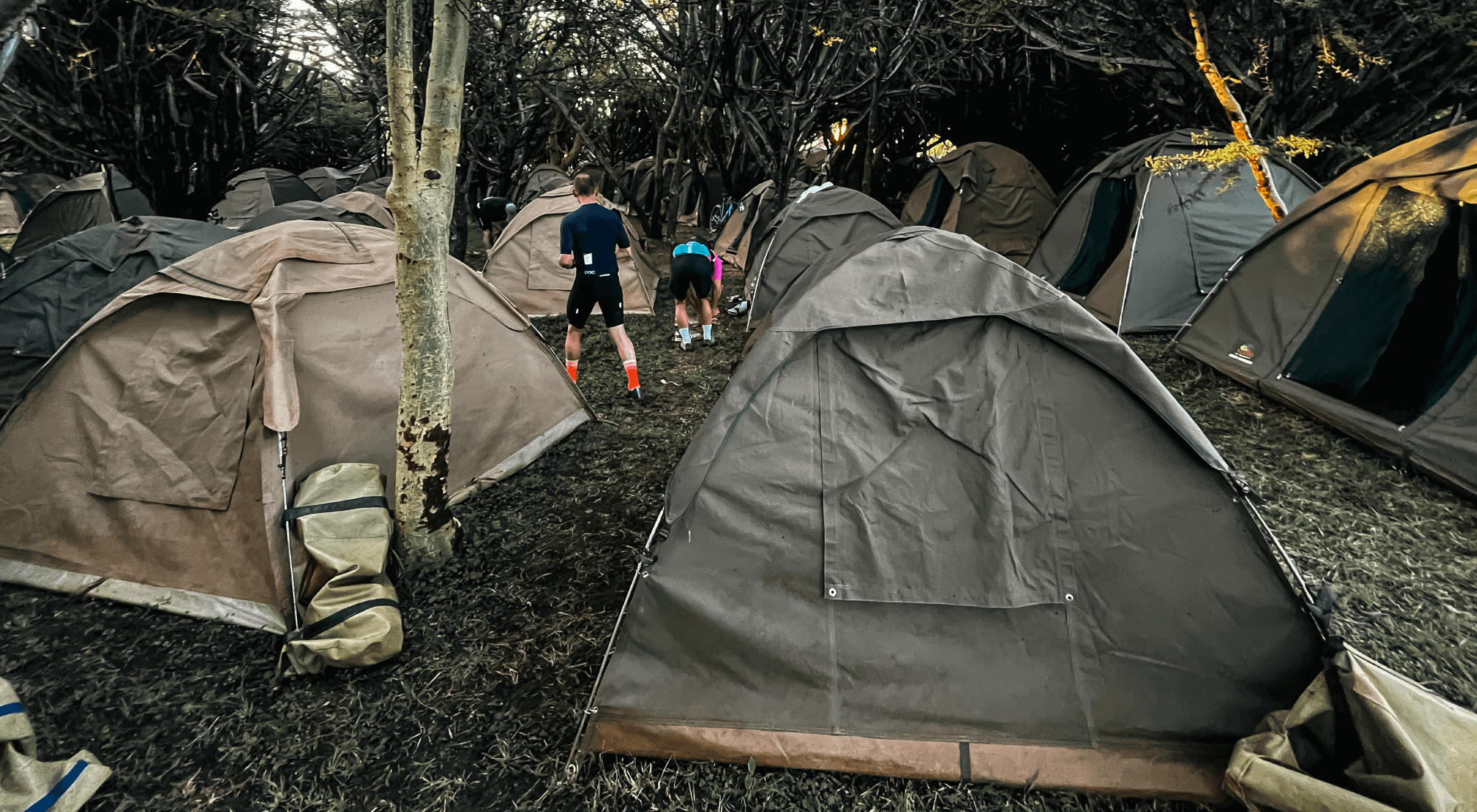

We started the final stage at 7:30 am, it was a wet and misty morning, it had rained through the night and once again I’d left my towel and shoes outside. No bother. I’ve come to terms with my failings and have passed caring about putting on wet shoes or needing a dry towel. I saw Rob first thing when I stepped out from my damp tent into the wet grass, he’d already had breakfast and collected his bike from the cleaning station. I told him straight away that I’d be riding with him, “You sure?” I told him yes, I’d had my “fun” the previous two stages and wanted to make sure he got to the finish, that’s my principal motivation for being here after all. I couldn’t have helped him get through the previous two stages as it was all down to him and his climbing and descending. Whereas the final stage gave some opportunity for drafting, and he’d need me for the morale as I knew he was tired and broken, as nearly everyone was.

Once in a lifetime experience

I have to interrupt my flow here as the previous paragraphs were technically demanding to write on an overland truck on Kenyan roads, I gave up a few hours ago, and I’ll be having to go back through and correct random keyboard slips. Trying again now just to give some context to this day and the length of this bus journey. It’s 19:57, we set off at 11:00, and we just concluded climbing out of the Rift Valley. We’ve been on the bus for nine hours, when I say on, I mean in, or in the vicinity of…

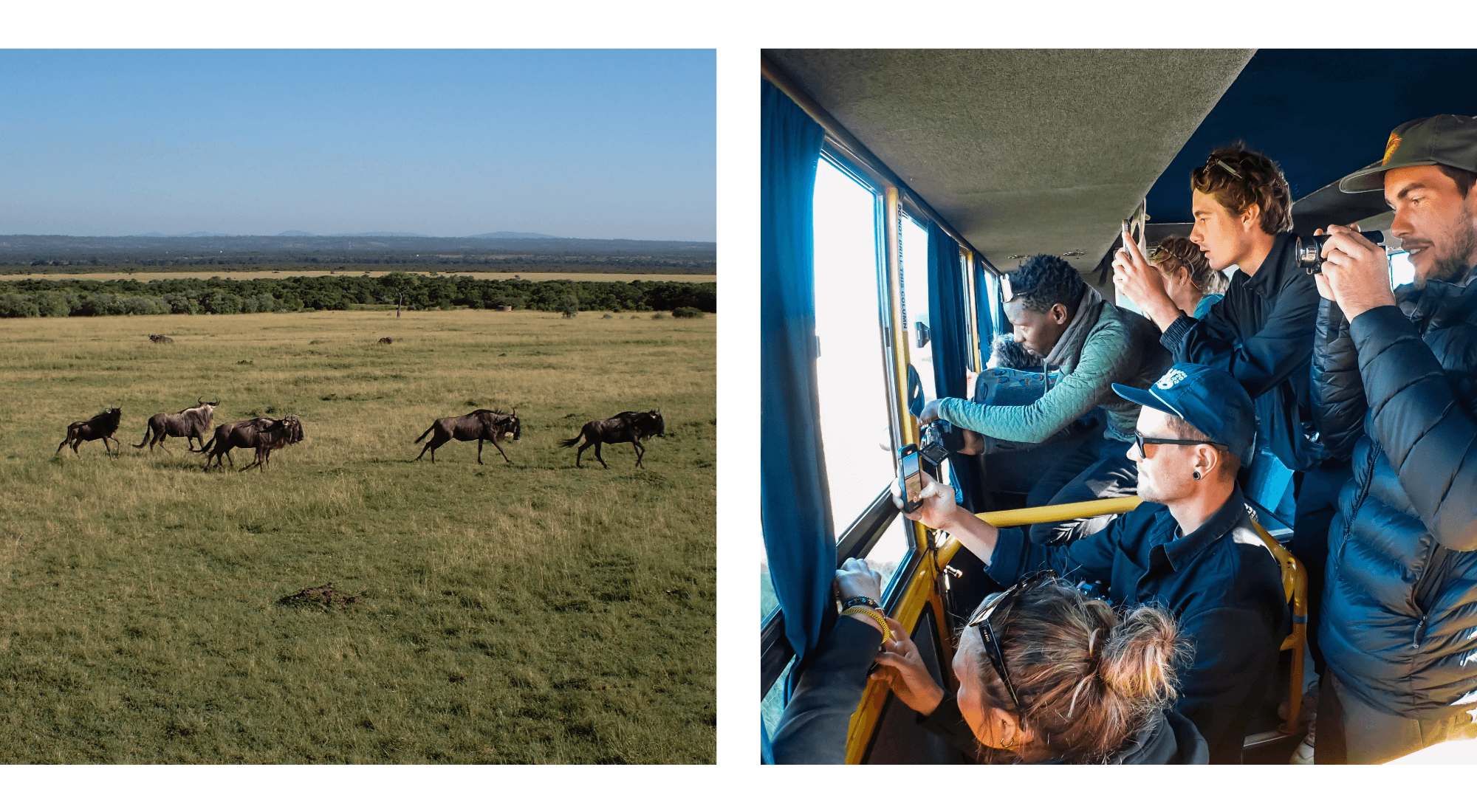

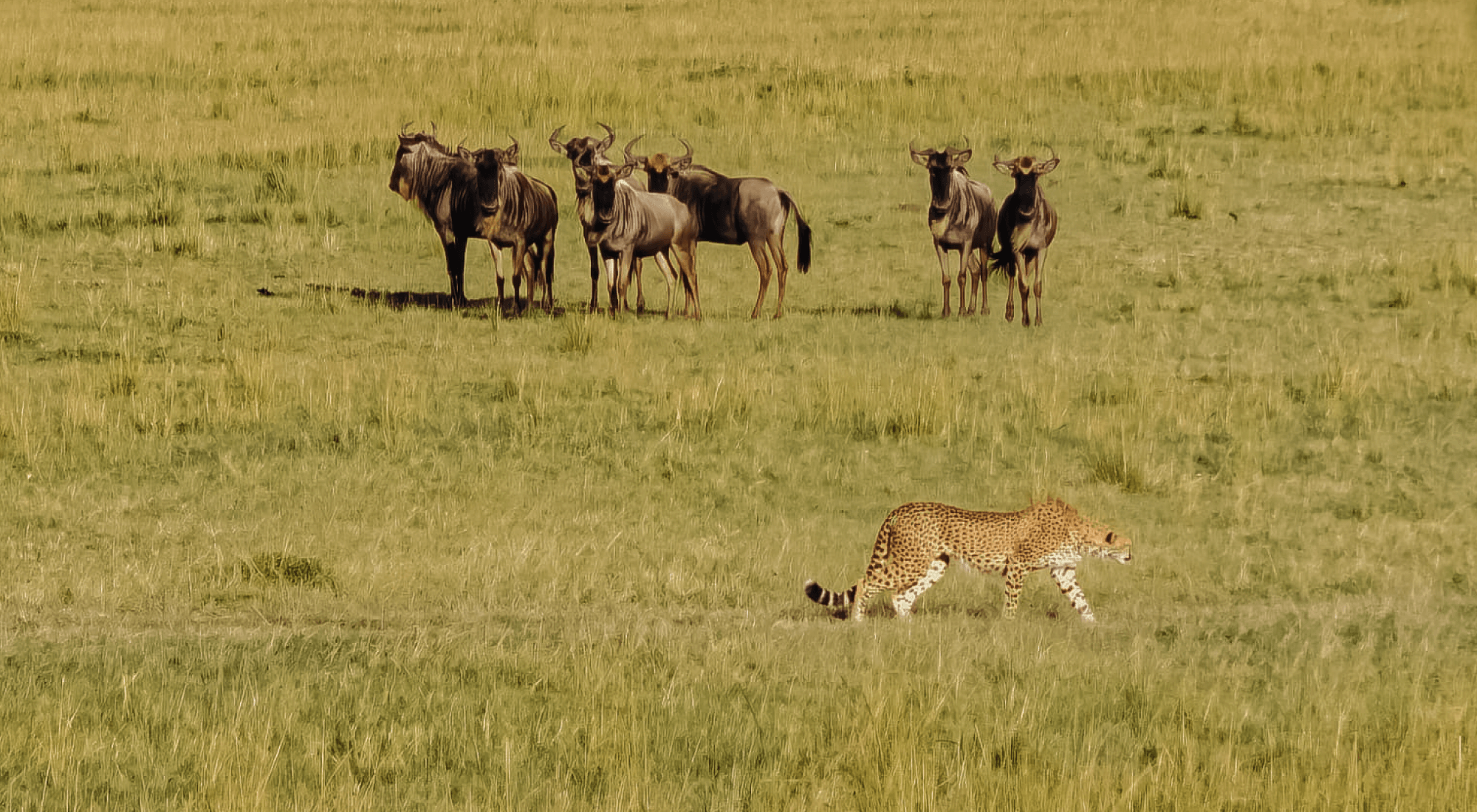

What I haven’t mentioned is that we got up at 6 am this morning to go on a 3-hour safari, we saw cheetahs stalking wildebeest, amazing to witness and a rare sight we’re told. Add that to this journey and the extra hour we have till arrival and that’s 14 hours on a bus today, let’s call it Stage 5. It says a lot about the people here that we almost all got up and went on safari after four of the hardest days most have ever had on a bike, yet still no one is complaining, although it’s very quiet on the bus currently.

When we eventually got to the hotel, I collected my bike and suitcase and had a 45-minute taxi ride to Nairobi airport, a 2-hour wait, then set off on my flight to Barcelona via Doha… Then up to Girona, unpack, repack, and off to the UK that evening to see the family before heading off to the Tour on Friday. Anyway, regaling you with this to put in context the format of this diary as it’s stop-starting in line with the journey and I wanted to reveal the circumstances.

Focused on the finish

I’m now in Nairobi airport, and so back to the race. Rob and I set off from the rear in a relaxed yet determined manner. No heroics, steadfast consistency and conservatism being the recipe for the day. I learned after the race when speaking to Mattia De Marchi, the leader starting the day, that his competition had chosen the tactic of exploding off the start line - his main opposition being Hans Becking, one the best mountain bikers in the world. Mountain bikers are trained to go fast from the gun, their events being relatively short and intense. Hans and his friends decided the best way of dislodging Mattia and gaining back eight minutes was to put him under pressure from the get-go. It worked, Hans ended up putting ten minutes into Mattia, taking the overall by two, but that’s another story. Rob and I were oblivious to that race. We had a job to do.

We rolled out at the pace we intended to maintain all day, no exploding for us. Those first few kilometers were quite strange for me, being back with Rob meant that I was well within myself and had full bandwidth to see beyond the riding. The first part of the race involved retracing the final of Stage 3, where I’d been riding into the headwind for fun, which had been in the afternoon, this was the early morning.

Facing realities

Whereas the previous day there had been barely anybody out there, today it was busy with children walking to school. They were all wearing a dark red uniform, and in small groups, occasionally individuals. I knew that most children walked to school in Kenya, sometimes large distances, yet I’d never witnessed it. It went on for kilometers, I’m guessing nearly 10 km, and it didn’t stop.

There was nothing out there, it was empty, I had no idea where they’d come from or where they were going. The more it went on the more my emotions got mixed up. I became very introspective, trying to work out what I was feeling. There was a huge admiration and respect for those children, how much they have to overcome, and how many challenges they face. It also made me extremely grateful for my good fortune and my children’s life.

Yet beyond that there was embarrassment, my privilege shamed me. There were clearly children who walked hours each day to and from school, something unimaginable where I live, where I’m from, and here I was riding a very expensive bike, in very expensive kit, for fun: for the experience. I may have taken this out on Rob a bit.

Keep pedaling!

It’s not easy to follow a wheel on gravel unless you have well-practiced skills, on the road Rob could hide in my pocket, he can hold a wheel so well, but on gravel, he can’t. He isn’t confident enough yet to react quickly to the unexpected that can quickly arise on mixed terrain, especially Migration madness. So he sits off my wheel, and before long that slips a bit further back, and even further if it descends.

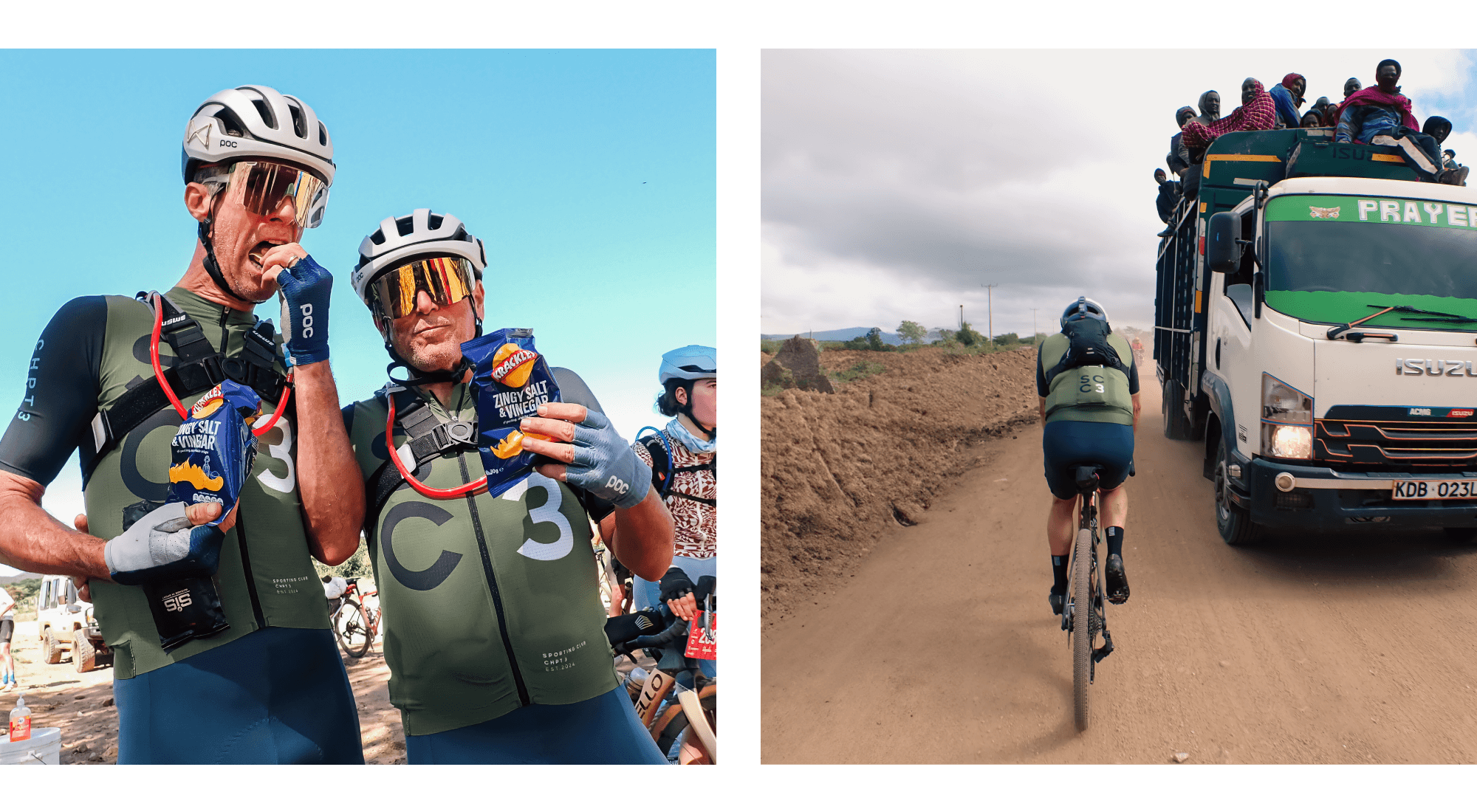

I’d find myself at 100, maybe 200m in front of him, I’d stop pedaling and look back and see he’d stop pedaling. I’d brake, let him come back to me, and instead of just starting it over again as I’d done before I said to him, “Rob, you’ve got to pedal. We’ve got to keep pedaling. This is what people do at the back, they stop pedaling when it’s easy, we’ve got to pedal when it’s easy, that’s where we make the time.” Can’t remember what he replied, but from that moment on I just kept shouting, “PEDAL ROB! We’ve got to make time!” Felt a little bad about it, I was in a strange mood.

I wasn’t all bad cop, in fact, I was mostly good cop. I was very encouraging, if I may say so myself. I got him to ride through water crossings, and there were more than I could count, first one of these he had his one and only crash of the entire four stages, splashing down beautifully. Which was very funny. He learned though, and the next crossing he was dandy, I got it on film with me shouting, “SEND IT ROB!” He did, not extreme games send, more of a gentle and quiet slide through the letterbox, delivered all the same.

The day was long, eight hours in total, we had one section of tarmac that lasted about 5 km, which was like a little piece of heaven, even if there was a serious head/crosswind, roadie Rob came into his own, tucked up so close to the left side of my back wheel that I could feel him. We had a tailwind most of the day, I could imagine how fast it would be at the front; must have been crazy fun. Yet even the tailwind could only do so much. The final 30 km were brutal, up there with the toughest of Migration, we were riding on roads that were essentially rock fields. It felt like the tailwind had disappeared, it was a miserable slog battling with the bike, hating life. By this point both Rob and I were exhausted, Rob physically more than me for sure, but both of us shared the mental fatigue. The final 15 km felt like they’d never end.

Lingering memories

It looks like Blade Runner 2049 out the plane window, welcome to Qatar. I fell asleep shortly after writing “never end” and was woken up for landing. I remembered something about our ride on that final stage that I’d forgotten. Rob and I had time to talk to each other, the sort of talks you only have on a bike where your barriers are down and what is said on the bike stays on the bike. We talked about our first meeting in 2015, we’d met down in the south of Spain, where Rob was delivering bikes to One Pro Cycling, the first team he sponsored, at their training camp.

Rob had transported the bikes himself and was helping the mechanics. I noticed that. I was in my first year out of pro cycling, and Baden Cooke (another former pro cyclist) had introduced me to Rob. I liked him and his vision, it tied in with what I wanted to do with CHPT3. I was one of the first, if not the first, Factor athletes. Looking back, deep in Kenya, riding Factor bikes, wearing CHPT3 kit, we both agreed we were proud of what we’d accomplished, yet we also came to terms with the fact that we are different from Rob and David who founded their brands back in 2015.

We’d both wanted to prove something, do something different, do things our own way. Yet we were both inexperienced, doubting our vision and abilities at times, and occasionally putting trust in the wrong people, people who told us they knew better. Ultimately, we’ve learned to trust ourselves, yet it’s taken time and meant enduring hard knocks. It has tired us out in our own different ways. I recognized now that the reason for this trip was for Rob to disconnect, he has been off email the entire week, something he said he hasn’t done since he founded Factor. I began to understand why he’d asked me to do this with him. Factor is in an amazing place now, and I guess he feels he can give himself some space, I mean, perhaps going to the Seychelles would have been preferable, but once a cyclist always a cyclist I guess, we find peace in hardship.

No Peak-End Rule here

We eventually finished the stage; Rob was angry, not relieved or euphoric, just pissed off at how horribly tough it had been those final kilometers. He got over it quickly, even though we had to wait three hours for our bags from the previous camp. There’s a thing called Peak-End Rule, it says we remember the peak and end moments of experiences so strongly that everything else blurs away from the memory. I don’t think that’s applicable to the Migration Race, because now sitting here in Doha Airport I find myself saturated with memories and moments that smother and extinguish the Peak-End Rule.

There were so many peaks and so many ends. Moments that are embedded in my mind. The overland transfers in and out of base camp alone will be a lifelong memory. The carnage of the mud field after 10km of the first stage. The thousand water crossings, racing with the lead women, going so deep that I couldn’t move for an hour when finishing, the vast landscapes and countless barefoot children smiling, waving, and shouting “Jambo!” The feeling that we were back in a world where people were closer to where we were supposed to be, part of nature rather than controlling it. The poverty in comparison to what I have always known, and the shame of not always fully appreciating the privilege I’ve been given by chance. The stillness and strength of the Maasai people, the Boda Bode motorbike riders who escorted us through everything on machines that have no right to be able to do what they made them do, they reminded me of that scene where a super modern 4x4 is being driven heroically in the middle of nowhere and comes across a local coming towards them in a Fiat Panda smoking a cigarette.

Final thoughts

I’m now sitting on my plane to Barcelona. I was going to go to the gym in the airport and do some sport to keep my body guessing, then reward myself with a proper shower and shave for the first time in a week, but got carried away writing this.

I want to finish with a message I received from Rob a few weeks ago, in reply to my tentatively asking him if he was sure he wanted to do the Migration Race, that maybe it was better we did it next year after he’d had more time to prepare, he replied, “I am by no means ready, but I’m also not putting things off anymore. There have been too many "next years" in my life. If you want to pass, I also fully understand, that your family is younger, and we are at different places in our lives. I do hope you can make it, though, and just bring a bunny. It can’t possibly be worse than Cape Epic.”

He was right about the bunny, I should have taken my son’s, although he’d have gotten wet in the tent. As for comparing it with Cape Epic, it was neither worse nor better, it was the same but different. Regards putting things off, that’s where he really hit the nail on the head.

As we get older, we perceive time to speed up, whereas it’s us who aren’t slowing down. We too, often get lost in the past or anxious about the future, forgetting that all we have is here and now in that very moment. When I was younger, I loved science fiction. Arthur C. Clarke was one of my favourite writers, I loved the worlds he created. I read his autobiography in my early twenties, and I can still remember vividly something he said. He was nearing the end of his life when he wrote it, and he said that what he treasured most in the world were his magic days. These were the memories of his life, the moments he’d never forget, that were so special he considered them magic. We are the architects of our lives, it’s up to us to create the experiences that slow everything down, allowing us to appreciate where we are and what we have. It’s in those moments that time changes, we take back control and feel alive and present, it’s where the memories that stay with us forever are made: our magic days. The Migration Gravel Race was a magic day machine. Thank you, Rob, and well done old boy. I know it wasn’t easy, we did it because it was hard.

Both the text and photos are by @David Millar

© 2025 Factor Bikes. All rights reserved / Privacy Policy |Terms